HackTheBox - White Rabbit

White Rabbit just retired on HackTheBox. This was an Insane-rated Linux machine, and it absolutely lived up to its difficulty. It was a interesting, multi-layered challenge that required so much enumeration (I didn’t really enjoy this patrt), and a deep dive into several different technologies. The path to user access was long and required chaining together a series of unique vulnerabilities. The root path was a classic but well executed reversing challenge involving a predictable pseudo-random number generator. In the end, White Rabbit is an excellent box for anyone looking to test their skills against a complex, real-world style engagement. Highly recommended!

Tl;Dr: To get the user flag, you first enumerate subdomains to find an Uptime Kuma instance. Bypassing its custom 404 filtering reveals a public status page leaking internal hostnames, including a Wiki. The Wiki details an n8n webhook workflow vulnerable to SQL injection but protected by an HMAC signature. The HMAC secret is found in a linked workflow file, allowing you to create a custom SQLMap tamper script to dump the database. The dump contains credentials for a Restic backup repository. You retrieve and crack a password-protected 7z archive from the backup to get an SSH key for the bob user inside a Docker container. A privilege escalation via sudo restic inside the container allows you to extract an SSH key for the user morpheus on the host, leading to the user flag.

For the root flag, you analyze a command from the previously dumped database log, which shows a neo-password-generator binary was used to set a user’s password at a specific time. By reversing the binary, you discover it uses a predictable, time-based seed for its pseudo-random number generation. You then write a script to reproduce all possible passwords generated within a small time window around the logged timestamp. Using this list, you bruteforce the neo user’s SSH password. Once logged in as neo, a quick check of sudo privileges reveals unrestricted root access, allowing you to escalate and read the root flag.

Alright! Let’s get into the details now!

First things first, let’s add the box’s IP to our hosts file:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ echo "10.10.11.63 whiterabbit.htb" >> /etc/hosts |

And let’s get started!

User Flag

Recon

Let’s kick things off with a classic nmap scan to see which ports are open on the box:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ nmap -sV -sT -sC whiterabbit.htb |

The scan reveals a classic web app on port 80, the standard SSH port 22, and another SSH service on port 2222. It’s worth noting that the SSH service on 2222 is running a slightly older version (3ubuntu13.5), which could be a potential vulnerability vector later on.

Opening http://whiterabbit.htb displays the following page:

It looks like a simple static website. The page describes the company’s pentesting services and mentions tools they use, such as GoPhish, n8n, and Uptime Kuma. Let’s keep that in mind, it could be a good hint for the reconnaissance phase.

With the basic port scan complete, we can move on to deeper enumeration.

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ nuclei -u http://whiterabbit.htb |

Running nuclei didn’t yield any interesting results, so I proceeded with directory and file enumeration to find hidden content:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ gobuster dir -u "http://whiterabbit.htb" -x sql,php,txt,html -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/big.txt |

No results here either, even with a larger wordlist. Since directory busting was a dead end, I shifted my focus to subdomain enumeration. After manually trying subdomains like n8n.whiterabbit.htb and gophish.whiterabbit.htb without success, I decided to automate the process with ffuf:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ ffuf -u http://whiterabbit.htb/ -H 'Host: FUZZ.whiterabbit.htb' -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/bitquark-subdomains-top100000.txt -fs 0 |

Bingo! We found one subdomain: status.whiterabbit.htb. Let’s add it to our hosts file:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ echo "10.10.11.63 status.whiterabbit.htb" >> /etc/hosts |

Uptime Kuma Discovery

This leads us to a login page for Uptime Kuma:

The login form looks solid, and the Uptime Kuma version is recent, with no obvious publicly available exploits. Given that we have nothing else so far, let’s keep enumerating this subdomain.

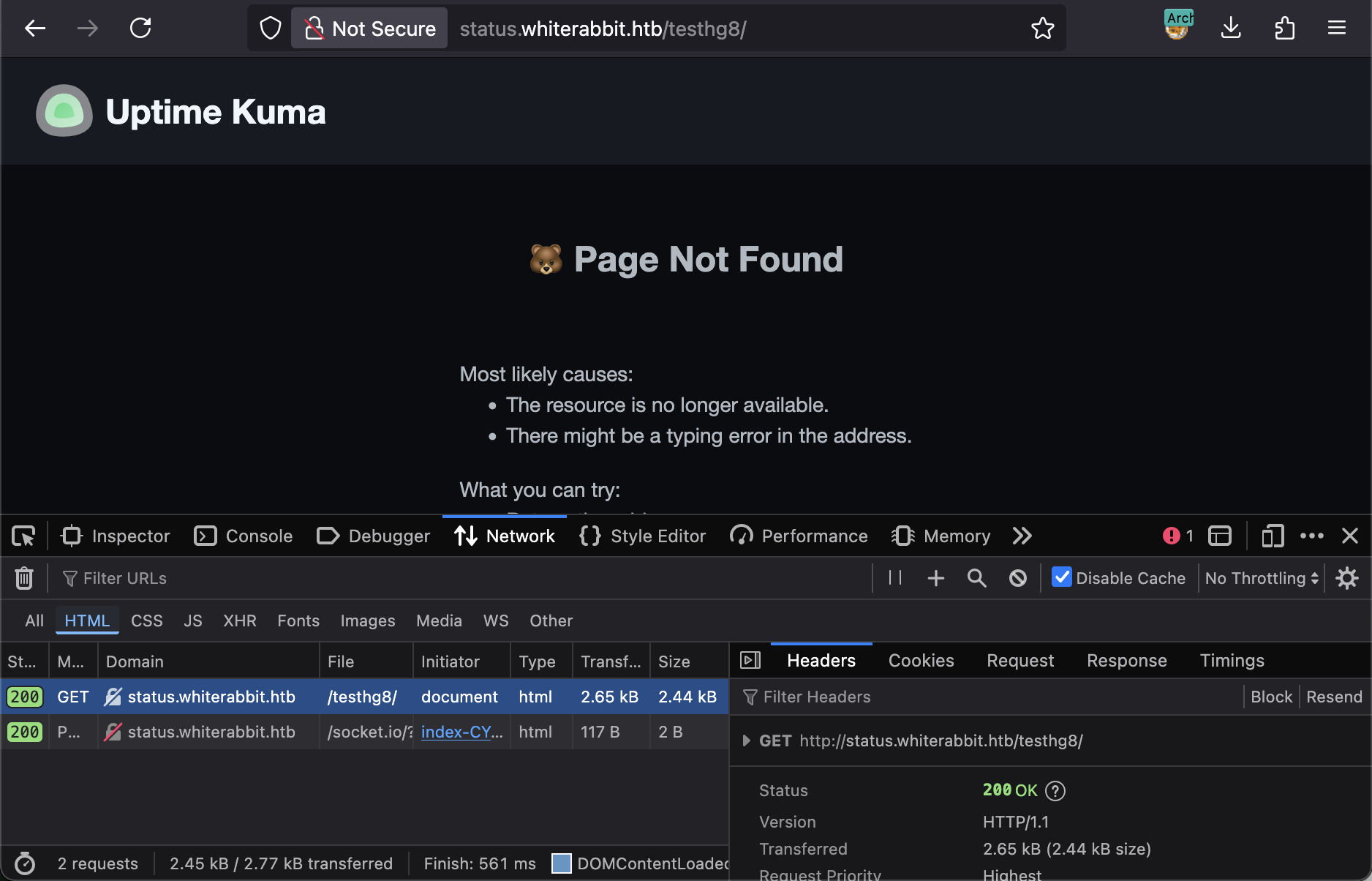

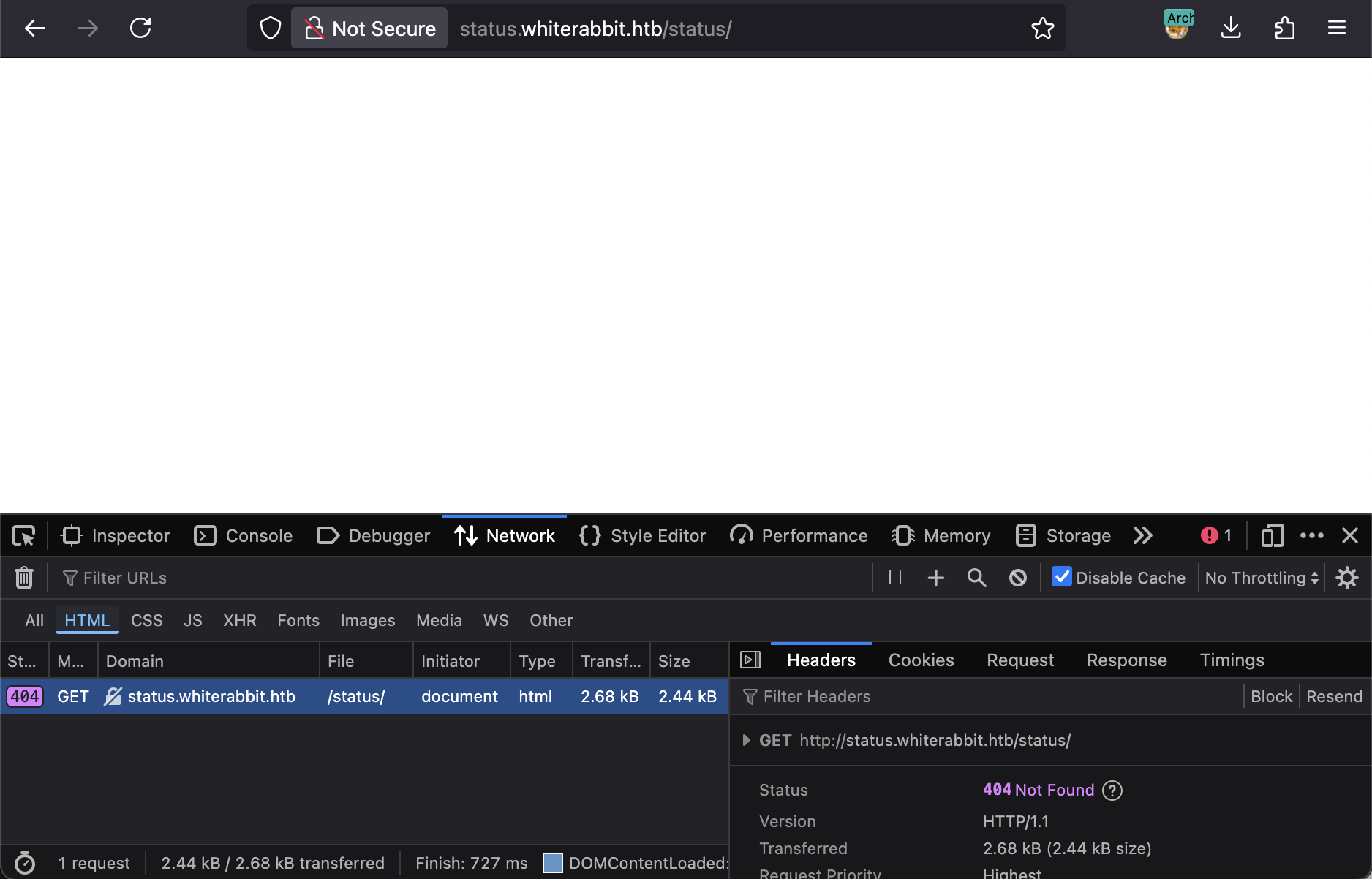

The enumeration was tricky because the Uptime Kuma instance returns a 200 OK status code even for non-existent pages, displaying a ‘404 Not Found’ message in the page body.

To work around this, I had to filter the ffuf results by the response size of the 404 page (-fs 2444), ignoring any pages that matched this size. Unfortunately, this also yielded no results.

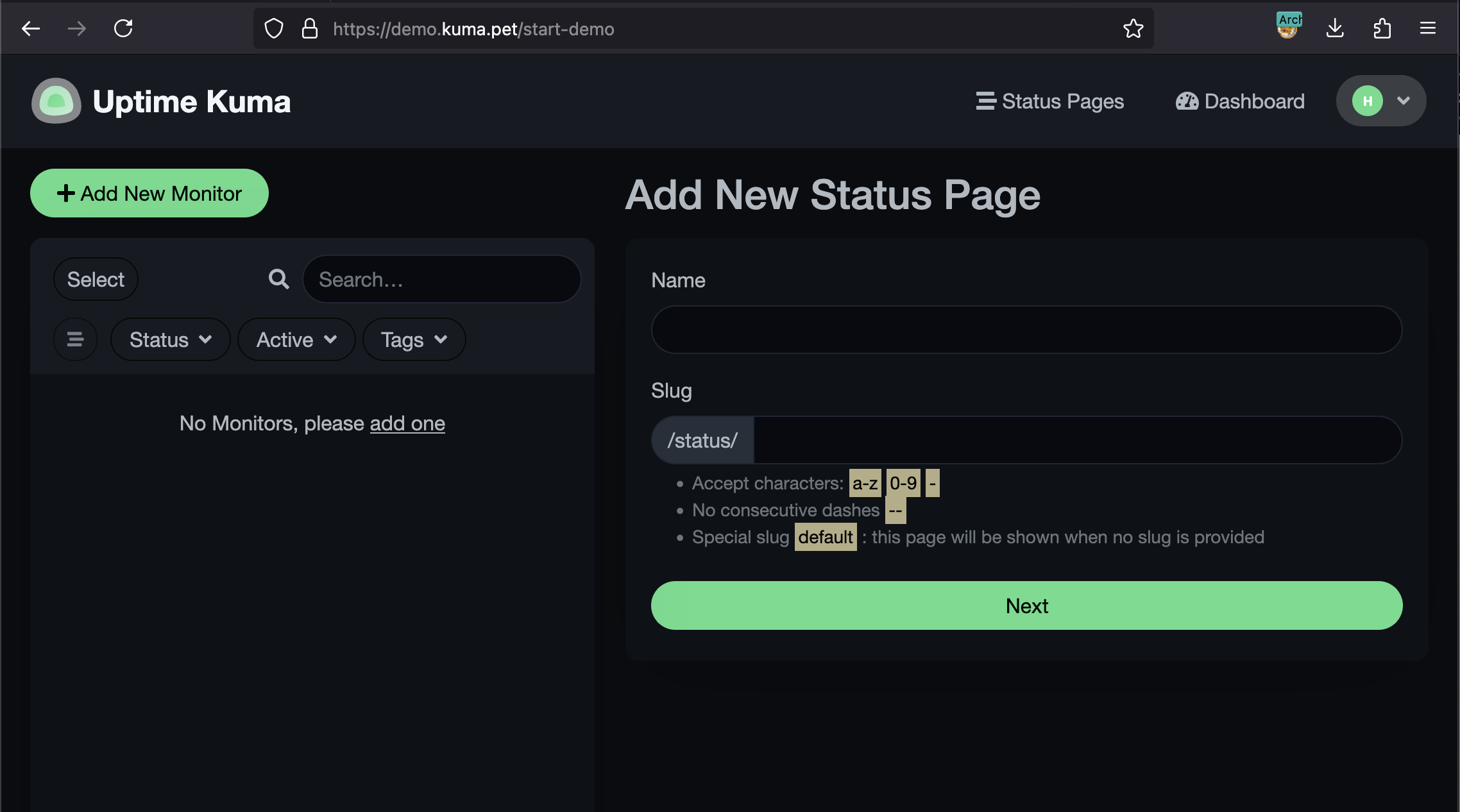

At this point, I was unsure how to progress. I decided to check the official Uptime Kuma documentation and noticed they have a demo page. I hoped that exploring the admin dashboard on the demo might reveal some default paths or functionalities I could test on the target.

There isn’t much to exploit in the admin panel itself—after all, it’s just a monitoring tool. However, I noticed that when creating a new status page, its path is always prefixed with /status/:

When we visit http://status.whiterabbit.htb/status/, we get a blank page.

Why wasn’t this /status/ endpoint found during our enumeration? It turns out this page returns the same 200 OK status code and has the exact same content size (2444 bytes) as the standard ‘Not Found’ error page. Very sneaky.

This discovery means we can now try to enumerate potential status pages under this path.

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ ffuf -u http://status.whiterabbit.htb/status/FUZZ -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt -fs 2444 |

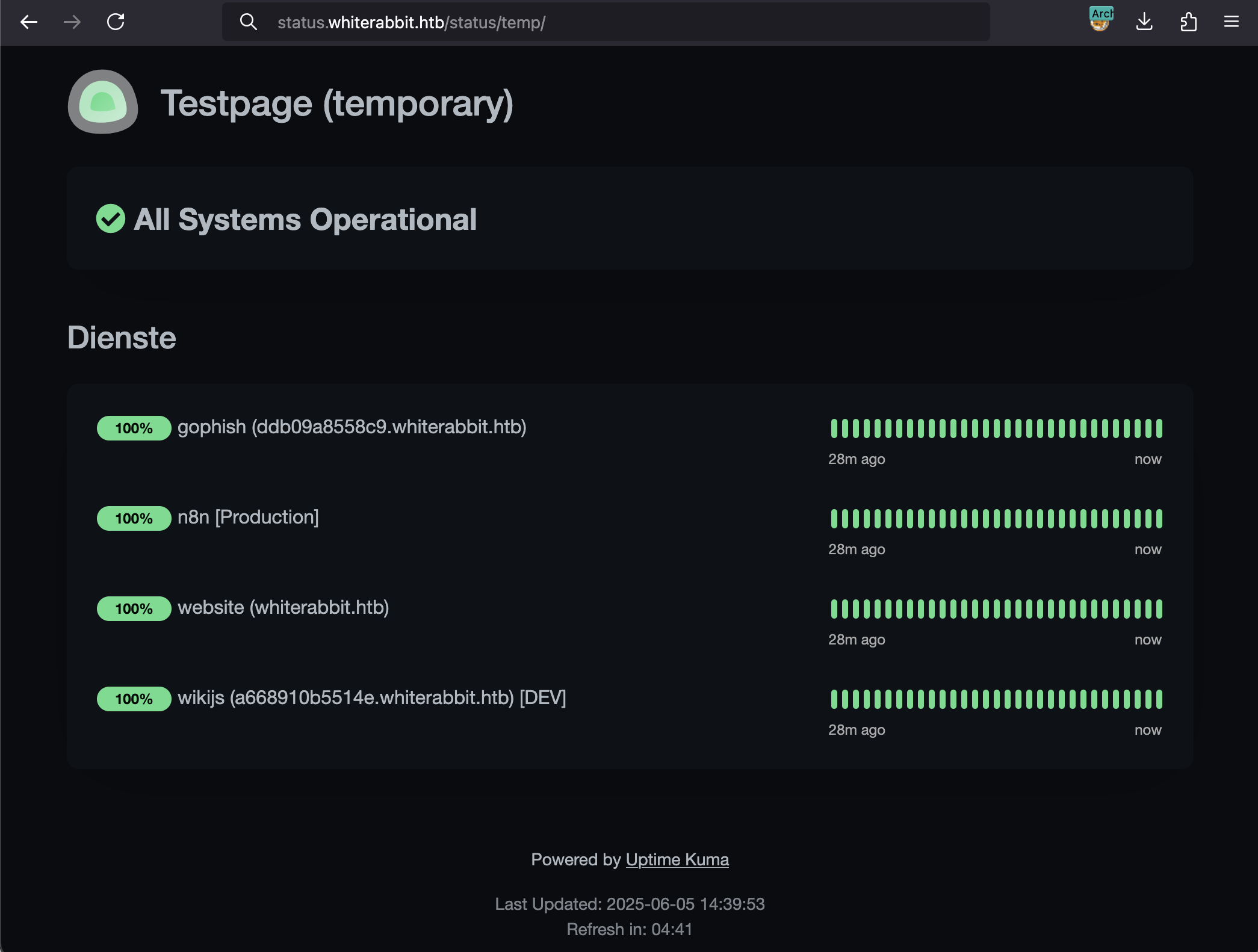

Opening http://status.whiterabbit.htb/status/temp shows the following page:

We finally get some useful information. The GoPhish and WikiJS subdomains look particularly promising. Let’s add them to our hosts file:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ echo "10.10.11.63 ddb09a8558c9.whiterabbit.htb" >> /etc/hosts |

GoPhish Webhooks & n8n Workflow

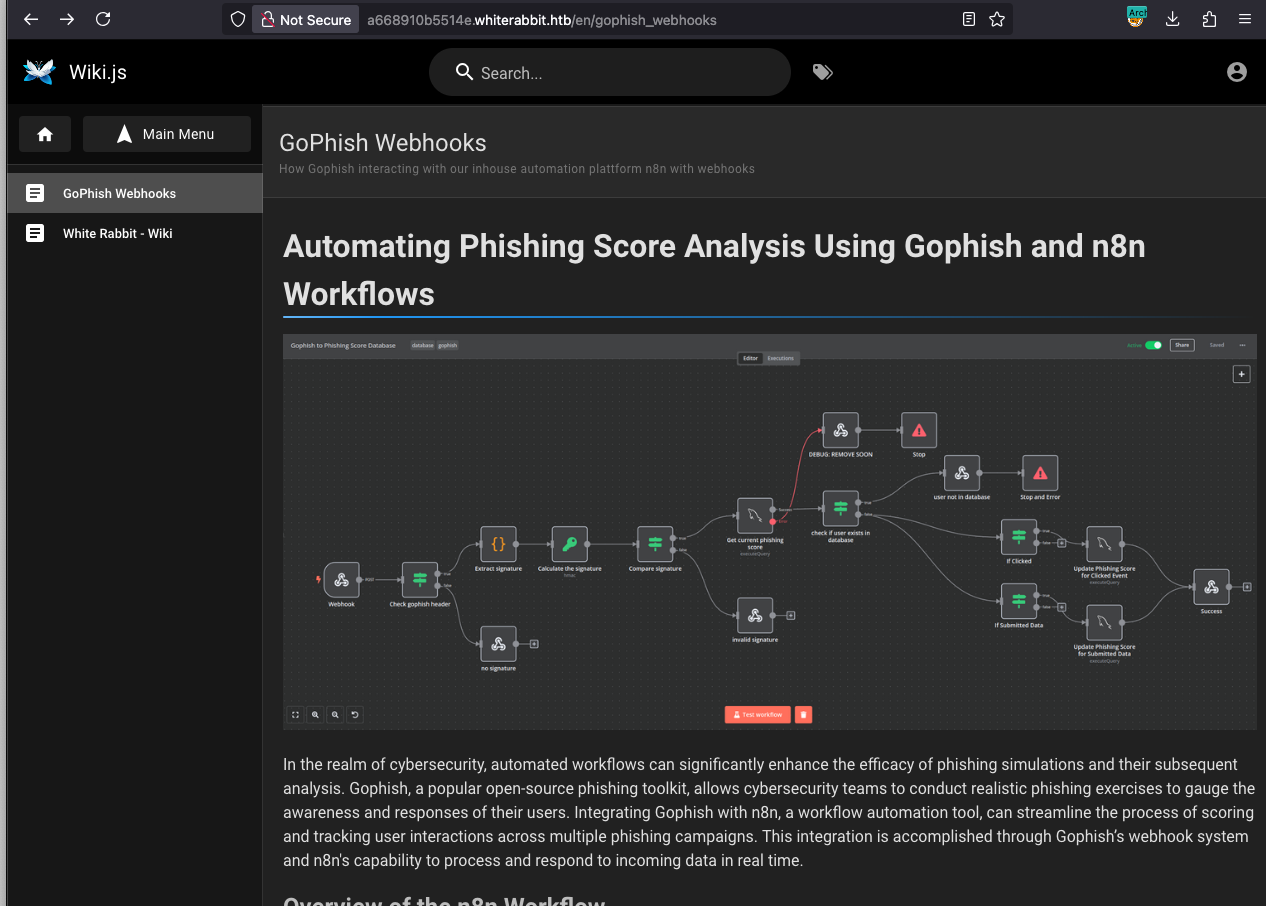

I decided to explore the Wiki first, as it’s a likely place to find sensitive information about the system’s architecture. Sure enough, I quickly stumbled upon a page titled “GoPhish Webhooks”:

The page describes a workflow where GoPhish sends event data to an n8n webhook. It even provides an example HTTP POST request:

1 | POST /webhook/d96af3a4-21bd-4bcb-bd34-37bfc67dfd1d |

The documentation also provides a link to a JSON file representing the complete n8n workflow: gophish_to_phishing_score_database.json.

SQL Injection in n8n Workflow

While reviewing the JSON workflow file, a few potential SQL injection vulnerability immediately stands out:

1 | [...] |

We can try to build a request with a SQL injection payload, but we immediately run into a signature validation error:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ curl -X POST \ |

This protection mechanism is also explained in the Wiki:

The x-gophish-signature in each request plays a crucial role in ensuring the integrity and security of the data received by n8n. This HMAC (Hash-Based Message Authentication Code) signature is generated by hashing the body of the request along with a secret key. The workflow’s verification of this signature ensures that the messages are not only intact but also are sent from an authorized source, significantly mitigating the risk of spoofed events for example SQLi attempts.

In short, every request to the webhook must be signed with a valid HMAC signature, or it will be rejected.

HMAC x-gophish-signature Generation

I remember seeing a secret key in the gophish_to_phishing_score_database.json file I downloaded earlier:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ grep "secret" gophish_to_phishing_score_database.json |

Let’s hope this is the correct secret. I can write a simple Python script to generate a valid signature for our test payload:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ cat hmac_generator.py |

With the newly generated signature, I can retry the request. And bingo!

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ curl -X POST \ |

SQLMap Tampering

The next logical step is to exploit this SQL injection to dump the database. The best tool for this job is SQLMap.

The challenge here is that every request sent by SQLMap needs a dynamically generated, valid x-gophish-signature header. My first thought was to use a proxy like mitmproxy to intercept SQLMap’s traffic and inject the signature on the fly. However, I realized later that a much cleaner solution is to use a SQLMap tamper script.

This Python script will be executed by SQLMap for every payload it sends. THe tamper script takes the SQLMap payload, embeds it into the JSON body, calculates the correct HMAC signature using our secret key, and adds the signature to the request headers.

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ cat gophish_signature_tamper.py |

Database Listing

With the tamper script in place, we can run SQLMap to list the available databases:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ sqlmap -u "http://28efa8f7df.whiterabbit.htb/webhook/d96af3a4-21bd-4bcb-bd34-37bfc67dfd1d" \ |

The phishing and temp databases look interesting. Using SQLMap to dump the tables from the temp database reveals a very interesting command_log table:

Database Dump

1 | Database: temp |

The command log contains interesting information: a subdomain for a restic repository and what appears to be its password. For those unfamiliar, restic is a command-line backup tool.

Restic Server Backup Dump

If we can access this restic repository, we might find sensitive files, like user credentials. First, we need to add this new subdomain (75951e6ff.whiterabbit.htb) to our /etc/hosts file. Then, we can try to list the contents of the latest backup snapshot.

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ restic -r rest:http://75951e6ff.whiterabbit.htb ls |

The bob.7z archive looks promising. Let’s download it:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ restic -r rest:http://75951e6ff.whiterabbit.htb dump latest /dev/shm/bob/ssh/bob.7z > bob.7z |

Bummer, the archive is password-protected. The restic password doesn’t work, and we don’t have any other credentials yet.

7-Zip Password Bruteforce

We know the archive likely contains an SSH key, so cracking it is our top priority. The old-school approach with john might do the job.

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ ./7z2john.pl ./htb/whiterabbit/bob.7z > hash.txt |

The password is 1q2w3e4r5t6y. Now we can extract the archive and inspect its contents. It contains an SSH key and a config file for a user named bob.

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ cat bob |

We’re in. But there’s no user flag yet. The hostname ebdce80611e9 suggests we’re inside a Docker container. Let’s see how we can pivot to the host machine.

Bob to Morpheus Pivot

Standard enumeration inside the container (sudo -l) reveals a key privilege escalation vector: the bob user can run restic as any user, without a password.

1 | bob@ebdce80611e9:/tmp$ sudo -l |

As we saw earlier, restic is a backup tool. If we can run it as root to create a backup of root-owned directories (like /root), we can then restore that backup to a location we control and read the files.

Let’s create a new, local restic repository in /tmp, back up the container’s /root directory to it, and then dump the contents.

1 | bob@ebdce80611e9:/tmp$ sudo restic -r /tmp/hg8-backup init |

4 files were added, which is a good sign. Let’s list the contents of our backup.

1 | bob@ebdce80611e9:/tmp$ sudo restic -r /tmp/hg8-backup ls latest |

Bingo! We’ve found an SSH key for a user named morpheus. Let’s extract the key, set the correct permissions, and use it to SSH into the main host (not the container) as morpheus.

1 | bob@ebdce80611e9:/tmp$ sudo restic -r /tmp/hg8-backup dump latest /root/morpheus > /tmp/morpheus_key |

And we have the user flag!

Root Flag

Recon

To get root, I remembered the command_log table from earlier. One particular entry caught my eye at the time:

1 | Database: temp |

This log shows that someone ran a password generator and piped the output to the passwd command for a user named neo.

Neo Password Generator Reversing

The neo-password-generator binary wasn’t present in the bob container, but as morpheus on the host machine, I can access and run it.

1 | morpheus@whiterabbit:~$ /opt/neo-password-generator/neo-password-generator |

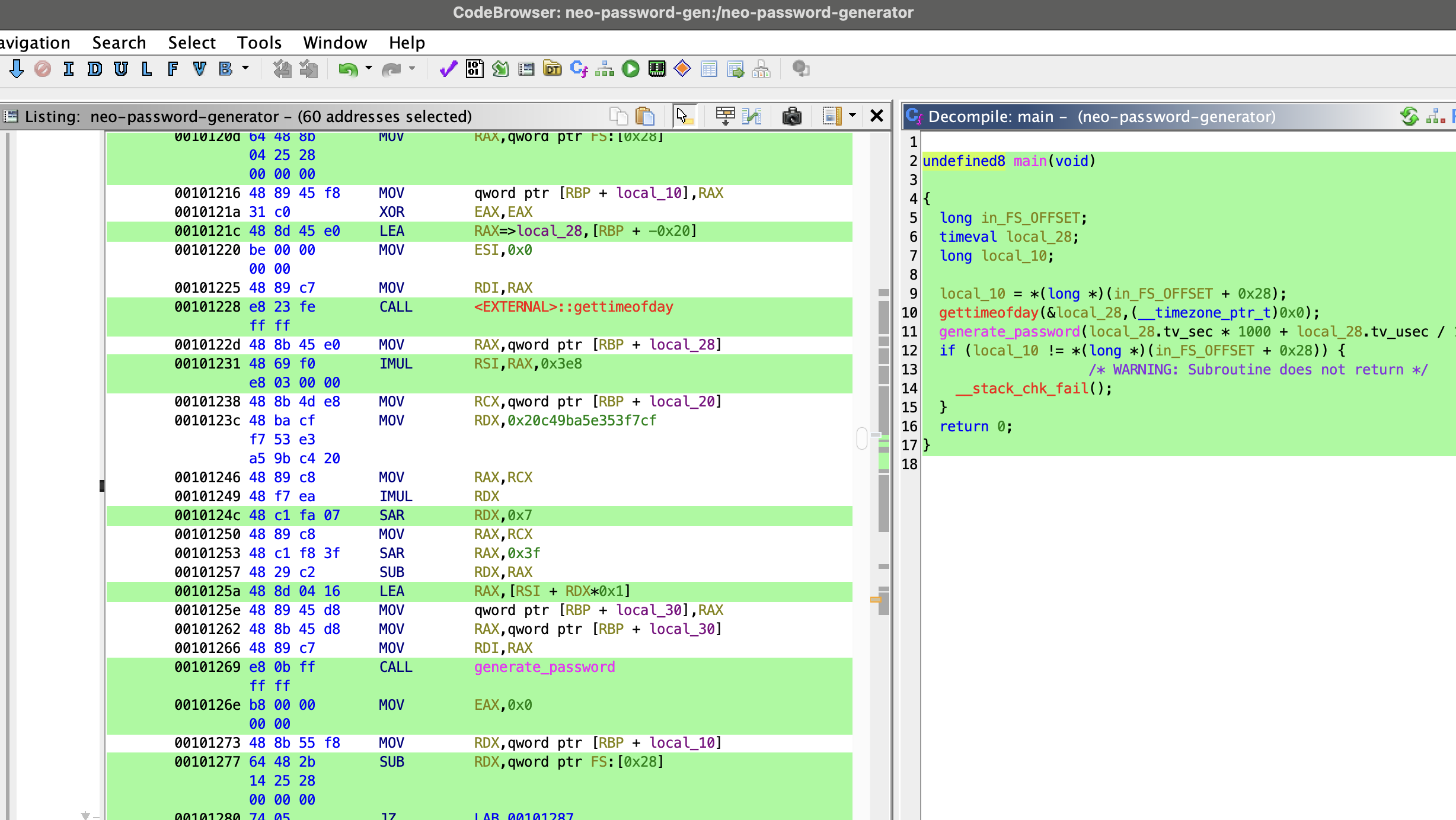

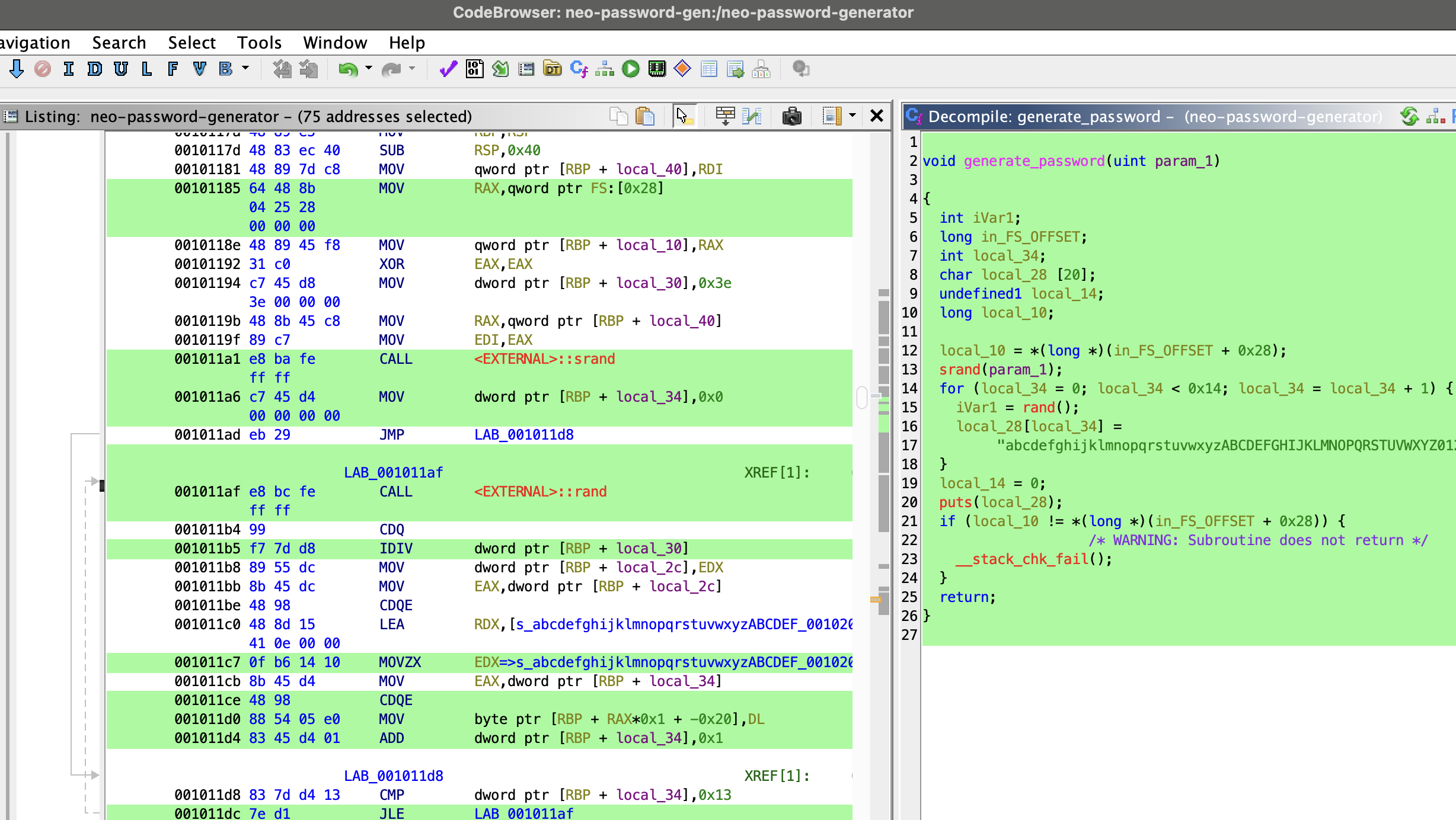

Well… it generates a random-looking password. Not very useful on its own. Let’s decompile it with Ghidra to see if we can find a weakness.

The binary has two main functions: main and generate_password.

Alright, let’s cleaned up the decompile code to make it more readable and understand what’s happening under the hood:

1 | int main(void) { |

The seed creation part is important. The developper wanted precision and just using the current second isn’t good enough, because if you run the program twice in the same second, you’d get the same password.

That’s why they used milliseconds.

The formula tv_sec * 1000 + tv_usec / 1000 converts the two separate values (tv_sec and tv_usec) into a single unit: total milliseconds since the epoch.

Now that we know how the seed is created, let’s focus on the password generation part:

1 | const char CHARACTER_SET[] = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789"; |

Let’s break down the logic:

- It takes the millisecond timestamp as a seed (from

main()). - It uses

srand(seed)to initialize the C library’s pseudo-random number generator (PRNG). - It loops 20 times, calling

rand()in each loop and using the result modulo 62 to pick a character. - It constructs and prints a 20-character password.

The main problem in this generator is its predictable seeding. The rand() function isn’t truly random; its sequence is entirely determined by the initial seed. We know from the command_log that the program was run around 2024-08-30 14:40:42. This means the seed was the number of milliseconds since the epoch at that moment.

However, the command likely wasn’t executed at exactly 14:40:42.000. There could be a delay of a few seconds, and the log’s timestamp might not be perfectly synchronized. Therefore, the strategy is:

- Calculate the Unix timestamp (in seconds) for

2024-08-30 14:40:42. - Create a search window—let’s say, 1 second before and 1 second after this time—to account for any delay.

- Iterate through every single millisecond in this window.

- For each millisecond timestamp (a potential seed), run our own implementation of the password generation logic.

- Try each generated password to log in to

neo‘s account.

Generate Potential Passwords for Neo

Here is the Python script I wrote to replicate the password generation logic and test every millisecond within our time window.

1 | import ctypes |

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ python neo-password-regenerate.py > neo-password-list.txt |

This gives us a solid list of potential passwords.

Bruteforce Neo’s SSH Account

With our password list ready, the next step is to bruteforce the SSH login for the user neo using hydra:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ hydra -l neo -P neo-password-list.txt -t 4 ssh://whiterabbit.htb -vV |

Bingo! One of the passwords worked:

1 | [hg8@archbook ~]$ ssh neo@whiterabbit.htb |

Note: Alternatively we could have written a script (such as suBF.sh) to bruteforce access directly from wihtin the box. It would have potentially be more discrete.

Privilege Escalation via Sudo

A quick check of sudo -l for privilege escalation paths reveals that neo has unrestricted root access. Not surprising for the chosen one ;)

1 | neo@whiterabbit:~$ sudo -l |

Getting the root flag is now trivial.

1 | neo@whiterabbit:~$ sudo su |

That’s it, folks! As always, feel free to reach out with any questions or feedback!

See you next time ;)

-hg8